In recent years, Canada has seen a clear rise in emigration. In 2024, the number of Canadians permanently leaving the country reached its highest level since 1967, according to population estimates.1 While Canada continues to attract high levels of immigration, this increase in emigration adds a new layer to discussions about affordability, labour markets, and long-term population trends.

In 2024, an estimated 106,134 Canadians emigrated, representing a 3.0% increase compared to 2023 and a 17.3% rise compared to 2019.

Current Trends in Canada's Emigration Rate

Tracking emigration from Canada is more complex than tracking immigration. While immigration statistics Canada, career indexes or the most popular names in Canada publishes detailed, program-level data each year, emigration is not recorded through a single exit system. Instead, Statistics Canada estimates emigration as part of its demographic accounting, using tax records, administrative data, and statistical modelling. This means emigration data is reliable at a trend level, but less granular than information on the immigration rate Canada, immigration levels, or canadian immigration statistics by year.

However, as mentioned earlier, emigration remained high throughout 2024. Data from Statistics Canada shows that the number of Canadians leaving the country stayed well above pre-pandemic levels, confirming that this is not just a short-term spike.

When compared with previous years, Statistics Canada’s estimates make it clear that emigration in 2024 was higher than both 2019 and 2023. These comparisons are based on the same population tracking methods used in earlier years, which allows trends over time to be assessed consistently.2

Looking more closely at how emigration unfolded over the year, quarterly estimates show that departures are not evenly spread across all months. Emigration tends to increase toward the second half of the year. This pattern points to planned, long-term moves rather than short-term or seasonal travel.

| Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Annual total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 21,331 | 19,602 | 30,675 | 18,852 | 90,460 |

| 2020 | 20,633 | 7,432 | 17,305 | 15,038 | 60,408 |

| 2021 | 17,184 | 17,100 | 26,453 | 22,620 | 83,357 |

| 2022 | 25,394 | 25,289 | 35,112 | 24,377 | 117,367 |

| 2023 | 28,289 | 25,513 | 39,617 | 23,948 | 117,367 |

| 2024 | 28,938 | 23,985 | 40,818 | 24,668 | 118,409 |

| 2025 | 29,816 | 24,714 | 41,203 | — | 95,733 (Q1–Q3) |

As shown in the table above, emigration dropped sharply in the beginning of 2020, reflecting global travel restrictions and reduced mobility during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. From 2021 onward, the number of Canadians leaving the country increased each year. By 2023 and 2024, emigration levels had not only recovered but also moved clearly above pre-pandemic levels, suggesting a sustained upward shift rather than a temporary rebound.3

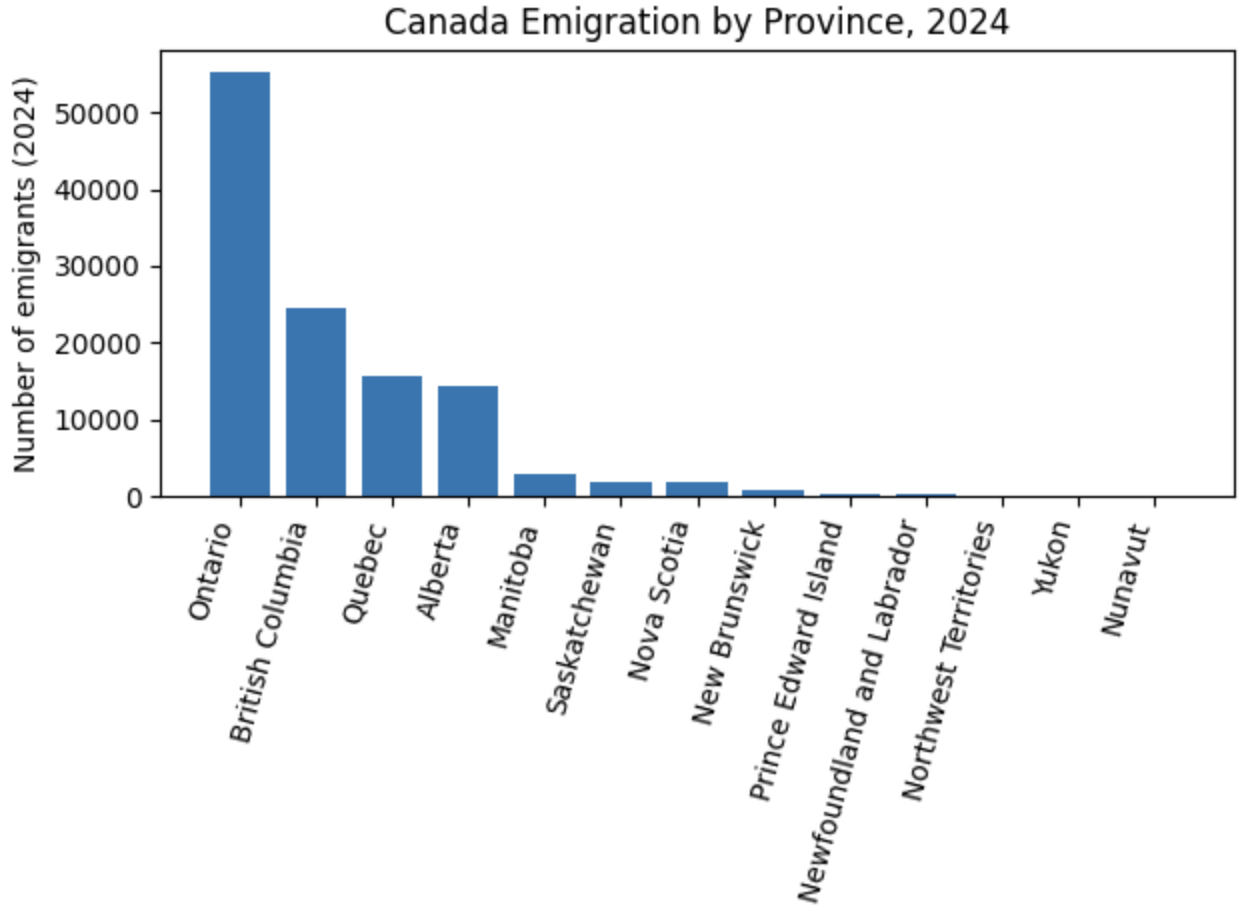

To understand where Canadians are leaving from, Table 2 breaks emigration down by province👇

| Province | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 338 | 252 | 354 | 337 | 275 | 263 | 224 |

| Prince Edward Island | 170 | 84 | 150 | 216 | 247 | 254 | 210 |

| Nova Scotia | 1,244 | 616 | 1,018 | 1,529 | 1,819 | 1,879 | 1,564 |

| New Brunswick | 696 | 431 | 656 | 873 | 914 | 899 | 739 |

| Quebec | 12,294 | 8,775 | 11,862 | 14,586 | 15,371 | 15,630 | 12,691 |

| Ontario | 41,193 | 27,138 | 37,691 | 52,682 | 55,267 | 55,225 | 44,758 |

| Manitoba | 2,544 | 1,938 | 3,043 | 3,374 | 3,032 | 3,053 | 2,575 |

| Saskatchewan | 2,066 | 1,298 | 1,669 | 2,029 | 2,046 | 1,994 | 1,622 |

| Alberta | 12,093 | 8,327 | 11,885 | 14,565 | 14,491 | 14,426 | 11,636 |

| British Columbia | 17,744 | 11,373 | 14,890 | 20,827 | 23,843 | 24,668 | 19,628 |

| Yukon | 54 | 35 | 98 | 83 | 26 | 32 | 27 |

| Northwest Territories | 24 | 20 | 27 | 60 | 79 | 86 | 59 |

| Nunavut | 0 | 4 | 14 | 21 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

The annual data shows clear regional patterns. Ontario and British Columbia consistently account for the largest share of Canadians leaving the country, largely reflecting their population size and higher international mobility. Quebec and Alberta follow with steady emigration totals, showing the same pandemic-related dip in 2020 and recovery in the years that followed.

In contrast, Atlantic Canada and the Prairie provinces record much lower emigration numbers overall. Smaller populations and more regionally focused labour markets contribute to stronger local retention. While emigration increased across all provinces after 2020, the relative ranking between provinces has remained stable, suggesting that long-term structural factors play a larger role than short-term regional changes.

Factors Influencing Emigration from Canada

While emigration data does not capture individual motivations directly, broader economic and social trends help explain why some Canadians choose to leave. Changes in labour markets, housing affordability, and education opportunities all play a role. These factors exist alongside Canada’s high immigration rate Canada and ambitious immigration levels, which continue to drive overall population growth despite rising emigration.

Cost of Living and Housing Affordability

Rising living costs have also contributed to emigration decisions. Housing prices and rents in major cities have increased faster than wages for many households. When compared with the average Canada household income, affordability pressures can make relocating to countries with lower housing costs or higher earning potential an appealing option.

Economic Opportunities Abroad

One of the most commonly cited reasons for emigration is access to better job opportunities and higher salaries abroad, particularly in countries such as the United States. Larger labour markets, higher compensation in certain industries, and faster career progression can make international moves attractive for highly skilled professionals.

This dynamic is often referred to as “brain drain”, where educated and experienced workers leave Canada to pursue opportunities elsewhere.4

Educational Pursuits and Long-Term Mobility

Education is another important driver of emigration. Some Canadians leave to pursue specialized academic programs, research opportunities, or institutions that are not available domestically. In many cases, studying abroad leads to longer-term settlement if graduates secure employment or residency after completing their education.

This outward flow exists alongside strong inward mobility. Canada hosts a large and growing population of international students and workers, which raises questions about how many temporary residents in Canada transition to permanent status. While emigration affects certain segments of the population, immigration remains the dominant force shaping Canada’s population outlook, including projections for the Canadian population in 2025.

Implications of Rising Emigration Rates

While emigration remains smaller than immigration, a sustained increase can still have meaningful effects. Changes in who leaves, where they leave from, and at what stage of life can influence labour markets, housing demand, and population structure. These implications are best understood over time, rather than as immediate shocks.

Economic Impact and the Labour Market

One of the most discussed implications of a rising Canada emigration rate is its potential impact on the labour market, particularly in sectors already facing recruitment challenges.

Between 2010 and 2019, immigrant workers accounted for more than 84 % of labour force growth, helping fill demand across professional, transportation, food services, and other key sectors.

When skilled and experienced workers leave the country, employers may encounter tighter talent pools, leading to recruitment pressures and slower productivity growth in certain fields. While emigration data does not capture individual motivations, workforce research shows that immigration has played a critical role in sustaining labour force growth.

Real Estate Market Effects

Emigration can also influence housing demand, particularly at a regional or local level. In areas with higher emigration, reduced demand for housing may ease pressure on prices or rental markets, especially if departures are concentrated among working-age households.

At the same time, housing markets are shaped by many factors, including immigration, internal migration, and housing supply. As a result, emigration alone is unlikely to drive major market shifts nationwide. Its impact is more likely to be felt unevenly, depending on regional population trends and local housing conditions.

Demographic Shifts and Long-Term Planning

Over time, higher emigration can contribute to changes in population composition. If emigration is concentrated among younger or working-age adults, it may affect age distribution, workforce participation, and demand for certain public services.

These shifts can have implications for long-term planning, including infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Understanding emigration alongside immigration and internal migration helps policymakers and communities plan more effectively for future population needs.

Comparative Analysis: Emigration vs. Immigration

To understand the Canada emigration rate, it helps to look at emigration and immigration side by side, using actual movement over time. While emigration has increased since the pandemic, it still happens at a much smaller scale than immigration. Based on Statistics Canada’s quarterly population estimates, annual emigration has typically ranged between around 80,000 and 120,000 people in recent years.

Both emigration and immigration dropped during the pandemic, but rose again once travel restrictions eased and international mobility returned. While emigration rose gradually after the pandemic, immigration increased much faster, driven by policy targets rather than individual timing.

During the pandemic, emigration fell to just 7,431 people in Q2 2020, as global travel stalled. Once mobility returned, outward movement rebounded sharply, reaching 41,208 emigrants in Q3 2025, while immigration surged even faster, peaking at 145,496 arrivals in Q1 2023.

This difference in scale is critical. Even when emigration reaches its highest recent levels, it remains far below immigration volumes. Canada welcomes hundreds of thousands of new permanent residents each year, alongside large numbers of temporary workers and international students. In 2021, more than 8.3 million people, 23% of the population, were immigrants or permanent residents, the highest share ever recorded.

That imbalance explains why immigration continues to drive population growth, even as more Canadians choose to leave.

Emigration is largely driven by individual choices and global mobility, which explains its sharp swings during and after the pandemic. Immigration, by contrast, is shaped by policy. Under the 2026–2028 Immigration Levels Plan, Canada continues to admit large numbers of permanent residents, even as temporary resident targets are reduced to ease pressure on housing and services.

Taken together, the data shows that rising emigration adds nuance to Canada’s migration story, but does not reverse it. Emigration can have localized or sector-specific effects, especially in high-mobility regions or professions.

However, its scale remains significantly smaller than immigration. As a result, Canada continues to experience net positive migration, with immigration remaining the dominant force shaping population growth, workforce size, and long-term demographic trends.

Addressing the Emigration Challenge

Canada’s rising emigration rate does not point to a sudden reversal, but to a more complex migration picture. More Canadians are choosing to leave, and that trend is now clearly visible in the data. At the same time, immigration continues to shape population growth and offset much of this outward movement.

What matters most is how these trends develop over time. If emigration remains elevated, especially among working-age or highly mobile groups, it could influence labour markets, housing demand, and regional population balance in more subtle ways. Tracking emigration alongside immigration and internal migration will therefore be increasingly important for understanding Canada’s long-term demographic direction.

References

- Read, T. (2025) Surge in Canadian emigration: Highest Levels since 1967, Coldwell Banker Horizon Realty. Available at: https://www.kelownarealestate.com/blog-posts/surge-in-canadian-emigration-highest-levels-since-1967.

- Government of Canada, S.C. (2025a) Annual demographic estimates: Canada, provinces and Territories, Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/91-215-X.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2025) Estimates of the components of International Migration, quarterly, Estimates of the components of international migration, quarterly. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710004001.

- Bains, S., Sekhon, G.K. and Kamal Deep Singh, R. (2025) Canada’s brain drain is surging fast and here are the top 10 reasons, Immigration News Canada. Available at: https://immigrationnewscanada.ca/canada-highly-skilled-immigrants-leaving/.

Summarize with AI: